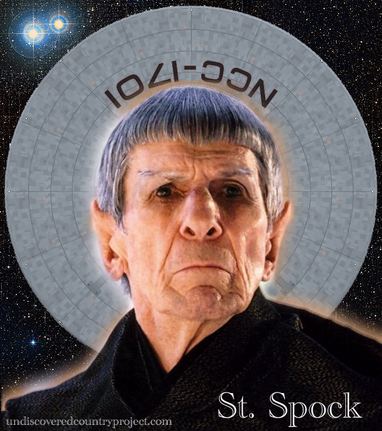

St. Spock of Vulcan – First Christ Figure of Star Trek

November 10th, 2011

I posted previously on Spock’s sacred and spiritual nature. But there’s more to him than being the Patron Saint of Star Trek. He’s also one of the series’ dual Christ figures. The symbolism is surprisingly deep (if unintentional), but I’ll hit the high points here.

To be clear, a Christ figure is any character in fiction who represents Christ in some way, either in whole or in part. Usually this is an intentional parallel but, as with much of what we’re discussing at UCP, sometimes we can find characters that reflect Christ whether they are specifically meant to do so or not.

The most common feature that makes a character a Christ figure is martyrdom. This is the most obvious way in which Spock fits the bill, giving his life for the crew of theEnterprise in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. This act alone would put Spock in the Christ figure ballpark, but a more complete Christ figure will also rise from the dead. Of course, Spock’s resurrection takes place in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock.

That’s all well and good, but Spock’s parallels with Christ don’t end at merely dying and rising again. Certain aspects of his character, along with the deeper significance of his sacrifice, both reinforce the metaphor.

First, Spock has a dual nature. Christ is described in Scripture as both human and Divine. In the same way, Spock is both human and Vulcan. Further, his Vulcan half is associated with a devoted, spiritual and elevated existence that may be seen as superhuman and therefore symbolically Divine. This is especially true, considering Vulcans’ greater physical strength, mental capacity, endurance and longevity. Jesus was born of a human woman, but his father is Yahweh. Similarly, Spock’s dual nature is represented by his parentage – his Vulcan (superhuman) father, Sarek, and his human mother, Amanda. Spock struggles with balancing this duality, just as Jesus did.

As I mentioned in my previous post, Spock is a deeply spiritual character who is a part of a ritualistic, religious culture. This reflects Jesus’ Jewish faith and culture, especially since Leonard Nimoy himself is Jewish and drew on his faith traditions to help shape Vulcan rituals. Spock is deeply invested in his Vulcan education and, just as Jesus impressed the elders at the temple in Jerusalem, shows much promise in the Vulcan Science Academy.

But Spock does not find his calling at the Science Academy, nor did Jesus find his within the temple walls. The 2009 film Star Trek takes this moment in Spock’s life further, showing his rejection of the Science Academy council’s ways as he refuses to enter the institution because he judges them to be unjust in much the way that Jesus clashed with religious authorities in Jerusalem. Both Spock and Jesus, therefore, find themselves at odds with the gatekeepers of their culture’s central institutions, even as they devote themselves to the values and teachings those institutions are meant to uphold.

Still, it is at the point of sacrifice that Spock bears his greatest resemblance to Christ and it is this moment that causes us to look for greater Christological significance in the character. As I mentioned, though, the significance of this element goes beyond death and resurrection. It’s one thing to die, even as a martyr for a cause, but Spock’s death reflects Christ’s on much more than superficial levels.

To be clear, a Christ figure is any character in fiction who represents Christ in some way, either in whole or in part. Usually this is an intentional parallel but, as with much of what we’re discussing at UCP, sometimes we can find characters that reflect Christ whether they are specifically meant to do so or not.

The most common feature that makes a character a Christ figure is martyrdom. This is the most obvious way in which Spock fits the bill, giving his life for the crew of theEnterprise in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. This act alone would put Spock in the Christ figure ballpark, but a more complete Christ figure will also rise from the dead. Of course, Spock’s resurrection takes place in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock.

That’s all well and good, but Spock’s parallels with Christ don’t end at merely dying and rising again. Certain aspects of his character, along with the deeper significance of his sacrifice, both reinforce the metaphor.

First, Spock has a dual nature. Christ is described in Scripture as both human and Divine. In the same way, Spock is both human and Vulcan. Further, his Vulcan half is associated with a devoted, spiritual and elevated existence that may be seen as superhuman and therefore symbolically Divine. This is especially true, considering Vulcans’ greater physical strength, mental capacity, endurance and longevity. Jesus was born of a human woman, but his father is Yahweh. Similarly, Spock’s dual nature is represented by his parentage – his Vulcan (superhuman) father, Sarek, and his human mother, Amanda. Spock struggles with balancing this duality, just as Jesus did.

As I mentioned in my previous post, Spock is a deeply spiritual character who is a part of a ritualistic, religious culture. This reflects Jesus’ Jewish faith and culture, especially since Leonard Nimoy himself is Jewish and drew on his faith traditions to help shape Vulcan rituals. Spock is deeply invested in his Vulcan education and, just as Jesus impressed the elders at the temple in Jerusalem, shows much promise in the Vulcan Science Academy.

But Spock does not find his calling at the Science Academy, nor did Jesus find his within the temple walls. The 2009 film Star Trek takes this moment in Spock’s life further, showing his rejection of the Science Academy council’s ways as he refuses to enter the institution because he judges them to be unjust in much the way that Jesus clashed with religious authorities in Jerusalem. Both Spock and Jesus, therefore, find themselves at odds with the gatekeepers of their culture’s central institutions, even as they devote themselves to the values and teachings those institutions are meant to uphold.

Still, it is at the point of sacrifice that Spock bears his greatest resemblance to Christ and it is this moment that causes us to look for greater Christological significance in the character. As I mentioned, though, the significance of this element goes beyond death and resurrection. It’s one thing to die, even as a martyr for a cause, but Spock’s death reflects Christ’s on much more than superficial levels.

First, no one kills Spock. He chooses to act in a manner that brings about his own death. Even though Jesus was executed, he still placed himself in a position that would guarantee his crucifixion. As he said, “No one takes [my life] away from me, but I lay it down of my own free will..” (John 10:17-18)

Spock’s sacrifice is certainly an act of salvation for the Enterprise crew, giving the ship just enough time to escape the Genesis wave. But the intent behind Khan’s attack is of a more personal nature and it is a personal redemption that Spock accomplishes. Khan comes from Kirk’s past seeking retribution for past sins, representing the determined reach and unrelenting grasp of damnation. “From Hell’s heart,” Khann says, “I stab at thee.” Khan represents the consequences, deserved or otherwise, of Kirk’s actions. He is Kirk’s judge and intends to be his executioner.

Throughout the film, the theme of age and death is prevalent, with a particular focus on Kirk growing older. Through the Genesis cave scene, youth is connected with Edenic imagery and associated with restoration. After Spock’s funeral, watching the sun rise on a garden-like new world called Genesis, Kirk says that he feels “young.” At this moment, Spock’s death has restored Kirk to a state of renewed life that is associated with Eden, a state from which Kirk had previously fallen. Moreover, Spock has died in Kirk’s place and so has delivered him from the consequences of his sin. In this way, his death is not just martyrdom, but substitutionary atonement.

Add to this that the crew of the Enterprise – and more specifically, her captain – is consistently symbolic of the human race in Star Trek, even to the point of the captain frequently being singled out as humankind’s representative, and Spock could be said to symbolically atone for the sins of all humanity. With this in mind, it seems no wonder, then, that the music at Spock’s funeral and in the accompanying the score is “Amazing Grace.”

So the image of Christ Spock represents is one who is of a dual nature from one human and one superhuman parent who finds himself at odds with the leadership of the core institutions of his ritualistic, religious culture. His is a deeply spiritual, meditative Christ figure who sets himself apart and willingly sacrifices his life for others, dying in their place to deliver them from the consequences of their sin and restore them to a state unmarred by age and death. And ultimately, he rises again, his tomb open and his grave clothes left behind.

Again, I’m not sure any of this is at all intentional. If it were, that intention would certainly not have come from Gene Roddenberry. But Spock’s status as a Christ figure is one area where I see what might be a kind of “Christ-haunting” in Star Trek. Somehow, despite (or perhaps because of) its efforts to move past religion, the series constantly bumps up against the Gospel. So, the fact that Spock is a Christ figure seems…only logical.

Spock’s sacrifice is certainly an act of salvation for the Enterprise crew, giving the ship just enough time to escape the Genesis wave. But the intent behind Khan’s attack is of a more personal nature and it is a personal redemption that Spock accomplishes. Khan comes from Kirk’s past seeking retribution for past sins, representing the determined reach and unrelenting grasp of damnation. “From Hell’s heart,” Khann says, “I stab at thee.” Khan represents the consequences, deserved or otherwise, of Kirk’s actions. He is Kirk’s judge and intends to be his executioner.

Throughout the film, the theme of age and death is prevalent, with a particular focus on Kirk growing older. Through the Genesis cave scene, youth is connected with Edenic imagery and associated with restoration. After Spock’s funeral, watching the sun rise on a garden-like new world called Genesis, Kirk says that he feels “young.” At this moment, Spock’s death has restored Kirk to a state of renewed life that is associated with Eden, a state from which Kirk had previously fallen. Moreover, Spock has died in Kirk’s place and so has delivered him from the consequences of his sin. In this way, his death is not just martyrdom, but substitutionary atonement.

Add to this that the crew of the Enterprise – and more specifically, her captain – is consistently symbolic of the human race in Star Trek, even to the point of the captain frequently being singled out as humankind’s representative, and Spock could be said to symbolically atone for the sins of all humanity. With this in mind, it seems no wonder, then, that the music at Spock’s funeral and in the accompanying the score is “Amazing Grace.”

So the image of Christ Spock represents is one who is of a dual nature from one human and one superhuman parent who finds himself at odds with the leadership of the core institutions of his ritualistic, religious culture. His is a deeply spiritual, meditative Christ figure who sets himself apart and willingly sacrifices his life for others, dying in their place to deliver them from the consequences of their sin and restore them to a state unmarred by age and death. And ultimately, he rises again, his tomb open and his grave clothes left behind.

Again, I’m not sure any of this is at all intentional. If it were, that intention would certainly not have come from Gene Roddenberry. But Spock’s status as a Christ figure is one area where I see what might be a kind of “Christ-haunting” in Star Trek. Somehow, despite (or perhaps because of) its efforts to move past religion, the series constantly bumps up against the Gospel. So, the fact that Spock is a Christ figure seems…only logical.

|

Want the full story on Spock as a Christ figure? Book me to give my presentation “Binary|Logic: The Dual Christ Figures of Star Trek and The Next Generation” at your school, church, convention or event! |

Comments (Closed in Archive)

- antodav says:

November 10, 2011 at 4:47 PM

Well, I take issue with some of your theology…but let’s set all that aside for a moment:

The only clear parallel between Christ and Spock can be found, as you mentioned, in his martyrdom at the end of Star Trek II and his resurrection in Star Trek III. Indeed, The reasoning for Spock’s death in Star Trek II, to save the crew of the Enterprise from destruction by the exploding Genesis device, exemplifies one of the key tenets of Christ’s doctrine, exemplified through the Atonement itself: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” (John 15:13). John 10:17-18 certainly applies to the manner of Spock’s death as well, as you described. I’m surprised that neither of those particular verses of scripture was actually quoted in the film, although I suppose I shouldn’t be, given the antipathy between the franchise and Christianity as a whole. In a way, Spock can be said to have even performed an atonement of his own, in that through his death the crew were saved and redeemed from their own sins (the sin of pride, the film implies, in Kirk’s case). Kirk’s statement “I feel…young.” and McCoy’s statement “He’s not really dead…so long as we remember him.” could be seen as an allusion to eternal life and to the necessity and importance of faith in salvation.

But I really think that’s about as far as it goes.

I take issue with the comparison of Spock’s Vulcan nature to Christ’s divinity, because while Spock was half-Vulcan and half-human, Christ was FULLY divine and FULLY human. He was the literal Son of God the Father (Elohim, not Yahweh or Jehovah as you stated), having been come to the Earth in the flesh, born of the Virgin Mary…this is quite different from Spock’s racially mixed nature, which was a source of conflict and contention for him, as opposed to Christ’s truly dualistic nature which was the source of all his power. There is nothing any of the Gospels to suggest that Christ ever struggled with balancing his human and divine nature; he had a perfect balance between the two from the beginning, as demonstrated by his willingness to teach the Gospel to the priests in Jerusalem when he was only 12 years old, boldly proclaiming that he was doing his “Father’s business”. (Luke 2:46-49).

Furthermore, I don’t accept this characterization of Sarek’s Vulcan nature as “superhuman”: Vulcans, in many ways, are less than human, because they are so unable to balance their emotions with their logic that they feel the need to repress their emotions entirely, which as frequently demonstrated on TOS, VOY, and ENT can and does serve as a significant handicap in certain situations. In some ways, Spock in his half-human, half-Vulcan form surpassed the abilities of his Father, and became “superhuman” in a sense, but only BECAUSE of his humanity, not in spite of it. This is another difference between Spock and Christ: Christ could never surpass or exceed the glory of his Father in Heaven, and as he himself stated, the Father is “greater than all” (John 10:29) including himself (John 14:28). Spock was constantly in disagreement and conflict with his father, all the way up until his Father’s death (TNG: “Unification”), which is a far cry from the relationship between Jesus and his Father, who were by his own account on several occasions “one”, i.e. they had a perfect unity of purpose, to the extent that to know one was to know the other.

Finally, while Spock may have shown some promise at the Vulcan Science Academy, I doubt that he actually got up and started teaching any classes there…big difference from the “promise” (fulfillment of promise, really) that the young Christ showed at the temple. As we saw in STXI, Spock was tortured both internally and externally by his split nature, and suffered terrible rejection at the hands of his peers. This scarred him and made him feel very sensitive about any suggestion that the human part of his essence constituted a handicap in some way. Spock’s choice to reject the Vulcan Science Academy’s offer of admission and instead enroll at Starfleet Academy could reflect in some way reflect the way that the Pharisees eventually rejected and crucified Jesus, or the manner in which Jesus rejected them and prophesied that the temple (meaning the temple of his body, but also the literal temple in Jerusalem) would be destroyed and rebuilt in three days, but that’s a bit of a stretch IMO.

Still, Spock is the best Christ figure that appears in the Star Trek franchise by far. Just not as good of one as you seem to want him to be, unfortunately.- Kevin C. Neece says:

November 11, 2011 at 6:28 PM

Thanks for your comment, Anthony! I really appreciate your perspective. I absolutely agree with much of what you have to say, but I think it’s important that I clarify my point of view.

The aspects of Spock’s character I mention here are not meant to have one-to-one correspondence with the aspects of Christ I’m comparing them to. All metaphors and analogies break down at some point and will in some details be unable to precisely correlate with what they represent. Otherwise, your Christ figure will be so similar to Christ, it may as well just be Jesus.

Beyond that broad statement, let me address your concerns specifically. (Your comments in bold.)

Well, I take issue with some of your theology

Of course you do! That is to be expected.

…but let’s set all that aside for a moment:

Agreed.

I take issue with the comparison of Spock’s Vulcan nature to Christ’s divinity, because while Spock was half-Vulcan and half-human, Christ was FULLY divine and FULLY human.

I’m not intending to imply that Christ was half human and half Divine. I’m just saying that both he and Spock are of two natures. There is no way for Spock to be fully human and fully Vulcan. Christ’s nature as fully human and fully Divine is a mystery, a paradox. Even if this similarity were intentional, I’ve no idea how, particularly in the Star Trek universe, a character could have such a nature. I’m sure it could be devised in some way or written into dialogue and never explained scientifically, but since there was no intent to replicate the nature of Christ and since there is no practical way to explain such a thing scientifically, it is enough that Spock is of two natures. Again, this needn’t be a complete one-to-one correlation. It’s only a symbol – or rather, an aspect of Spock’s character that I am choosing to read as a symbol. It merely reinforces the idea that there are deeper attendant details to the comparison than merely death and resurrection.

Elohim, not Yahweh or Jehovah as you stated

“Yahweh” is no more or less preferable, in my view, than “Elohim” as a name for God. Both “Yahweh” (which I used) and “Jehovah” (which I did not use) are based on a major Old Testament name for God whose Hebrew spelling is transliterated “YHWH” (or “JHVH”). In my opinion, “Jehovah” is based on the cruder transliteration of the two and therefore is a word I tend not to use. But really, “Jehovah” is perfectly acceptable. In the same way, “Yahweh” is just as good a name for God as “Elohim,” as are “God the Father,” “El Elyon,” “El Shaddai” and so forth. So, “Elohim” and “Yahweh” are generally considered synonyms (cf. Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms). That may not be your view for whatever reason, but we’ll leave that be.

There is nothing [in] any of the Gospels to suggest that Christ ever struggled with balancing his human and divine nature

Again, this may simply be a difference of interpretation or theology. I see the Garden of Gethsemane and the temptation in the desert as windows on what must have been a constant part of Jesus’ life – submitting his human will to the will of the Father. If we are to say that Jesus is fully human, we must expect that he had a human journey. Paul says that Christ was submissive and surrendered even to death on the cross rather than seeking equality with God (that is, in the greedy, human way Satan tempted him with in the desert). Because of this, Paul says, God has given him a name that is above every name. So, in my view, Jesus must necessarily have struggled against and overcome his human desires and temptation to sin. If he did not, then his moral perfection is a mere pageant. Why should he get credit for being blameless if he didn’t have to truly overcome temptation to get there? What is the value of his sinless state if it was just handed to him? When Jesus said, “It is accomplished,” I believe that he accomplished something – actually, a number of things. But one of them was resisting temptation to the last. He could have called 10,000 angels to rescue him from the cross, but he did not. That was an evidence of Divine origin as much as an accomplishment of human will. This, to me, is the reconciliation of his human and Divine natures and is essential to the Gospel. Again, you may disagree, but that’s okay.

Furthermore, I don’t accept this characterization of Sarek’s Vulcan nature as “superhuman”

My characterization was not exclusively of Sarek’s Vulcan nature, but of Vulcan ideals in general and the Vulcans’ evolution as a species. On the one hand, they are physically and mentally superior. That is simply a genetic fact. Primarily, though, I’m referring to Vulcans seeking an escape from baser animal instincts in favor of a life of peace. They seek a kind of elevated existence that expresses itself in spiritual, meditative and ritualistic practices and mindsets which are easily associated with the religious life of humans and a quest for spiritual transcendence. In this sense, Vulcan values may be seen as somehow elevated above mere existence. My use of the word “superhuman” is also something of a wink to Vulcans’ convictions about their own superiority to humans as a species. I actually think part of the point of Spock’s character is to show that the Vulcan way lacks some things that the human way provides and vice-versa. I’m not trying to say that Vulcans are Divine. I’m merely making the point that Spock’s Vulcan nature may be seen from at least a couple of perspectives as superhuman or lofty, not that all Vulcans are in all ways superior to humans. Remember also that this post is greatly abbreviated from larger ideas. There’s a lot more to go into about Star Trek’s views of humanity and Divinity. The point is, there’s a parent who represents an elevated ideal to which Spock strives and another parent who represents a humanity which he surrenders to that elevated ideal. Again, a mere symbol of a similar dynamic in Jesus.

Christ’s truly dualistic nature which was the source of all his power

I believe I understand what you mean here and agree. In fact, the same could be said of Spock, in a way. (Again, this is not exactly the same, just similar.) Spock reaches his maturity and is at his best when his human and Vulcan sides are reconciled, when he lives in both natures at once. For example, his sacrifice is the “logical” choice, to be sure. But it also represents the greatest expression of deep, human love. In the same way, Christ’s sacrifice exemplifies Divine love as well as the human act of Jesus surrendering his will to God’s. He is operating in the best of both humanity and Divinity.

However, I must say that the word “dualistic,” at least from the standpoint of philosophical terminology, is not accurate. Dualism sees a strong divide between two things that do not mix. What you are referring to, however (if I’m understanding you correctly), is Christ’s nature as simultaneously fully human and fully Divine. So, Christ’s nature is not dualistic, at least in the way that I understand that word. I recognize, of course, that you may be using that word according to the parameters of a different discipline or school of thought. Or perhaps you merely meant to say “dual.”

In some ways, Spock in his half-human, half-Vulcan form surpassed the abilities of his Father, and became “superhuman” in a sense, but only BECAUSE of his humanity, not in spite of it.

Agreed. I think that’s something Spock learns about himself: that his humanity is not holding him back, but is an essential element of his being. Similarly, Christ came as both God condescending to humanity and a human ascending to God. The kind of human life he led both proved his Divinity and earned him the name that is above every name. In other words, in Jesus are both perfect Divinity and perfect humanity.

This is another difference between Spock and Christ: Christ could never surpass or exceed the glory of his Father in Heaven … Spock was constantly in disagreement and conflict with his father, all the way up until his Father’s death (TNG: “Unification”), which is a far cry from the relationship between Jesus and his Father…

There are two points made here, but I’ll address them together. I never meant to set up Sarek as a metaphor for God. I simply said that, like Jesus, Spock’s two natures are each represented by one of his parents. The comparison ends there. As I said, all metaphors and analogies have their limits and eventually cannot exactly correlate in every detail with what they represent. If they could, they would no longer be symbols of things, but the things themselves. All that to say that of course Sarek and Spock’s relationship doesn’t reflect Jesus’ relationship with God the Father. It doesn’t have to, nor could it ever accurately do so, as the Trinity is a mystery. After all, Sarek is hardly analogous to God in almost any way. For that matter, Amanda isn’t a virgin either!

Finally, while Spock may have shown some promise at the Vulcan Science Academy, I doubt that he actually got up and started teaching any classes there…

Well we don’t know that, do we? But, once again, this is a difference in detail where I simply didn’t intend to imply that the two examples were a perfect match. All I said was that Jesus and Spock were both impressive in their studies, not that they were exactly the same.

Spock’s choice to reject the Vulcan Science Academy’s offer of admission and instead enroll at Starfleet Academy could reflect in some way reflect the way that the Pharisees eventually rejected and crucified Jesus, or the manner in which Jesus rejected them and prophesied that the temple (meaning the temple of his body, but also the literal temple in Jerusalem) would be destroyed and rebuilt in three days, but that’s a bit of a stretch IMO.

Well, again, I’m not meaning to say they are exactly the same. They’re just similar. They reflect one another in that Spock morally objected to the actions of the council and Jesus morally objected to the teachers of the law and Pharisees. The ways Jesus was different caused him to have conflict with religious authorities and the ways Spock was different caused him to have conflict with what might be seen as religious authorities in his culture. It’s really not anything more than that, nor did I claim that it was. The point is, they both chose to separate themselves from the central educational and (for all intents and purposes) religious institutions of their cultures, even though they could have chosen not to and would almost certainly have excelled within those institutions.

Thanks again for your comment! You make excellent arguments overall and I do not, for the most part, disagree with your reasoning. However, most of your objections are to things I did not intend to imply or are based on details that are simply asking too much of entirely unintentional symbolism. I think the correlations that are there are fascinating simply because, even though they were not intended, they exist on some level. There’s more to it than what I wrote in the post as well. At any rate, I hope this response clarified my intentions. Thanks for the challenge!

- Kevin C. Neece says:

- reneamac says:

November 15, 2011 at 12:02 PM

This was wonderful, a thoroughly enjoyable read!

I’m curious about examples of Christ’s struggling with his dual nature. I’m not inclined to disagree with you; I just suppose I haven’t given the matter much thought, and so I’m not coming up with textual examples for myself.- Kevin C. Neece says:

November 18, 2011 at 9:23 PM

Thanks! I’m glad you enjoyed it!

It’s less a large proclamation in Scripture and more a logical conclusion based on scriptural events and claims, not unlike the doctrine of the Trinity. If we accept that Jesus is fully human, we must necessarily read his struggles as human ones that nonetheless evidence his Divinity.

In the desert temptation, we read the story of Satan approaching Jesus in the desert and having a dialogue. But honestly? That doesn’t ring true to me. Jesus says in Luke 10 that “I saw Satan fall like lightning from Heaven.” He knows who the Devil is, where he comes from and whose side he’s on – his own. Old Scratch doesn’t approach Jesus face to face and say, “Hey, I’ve got an idea!” realistically expecting Jesus to say, “Okay!”

I see this as an internal struggle that happens inside Jesus, which he later related to his disciples (he had to since he was the only one there!) in hindsight terms. At the time, he thought, “I’m so hungry. So hungry. There’s no food. If all this is true and I have the power of the Almighty, I could turn those stones to bread!” But, the he remembers: “No, I’m here to be satiated only by the words of God.” When he tells the story, he tells it with the understanding that it was Satan who wanted him to follow his very human urges against the will of God. The whole temptation sequence is not Satan looking for proof that Jesus is God’s Messiah. It’s Jesus humanly desiring to understand that himself and Satan taking advantage of the moment. That’s how our human struggles go. We struggle to understand, to discover and submit to God’s will and Satan meets us at the weakest points of our humanity. Why should Jesus’ struggles have been any different?

In the same way, the Garden of Gethsemane clearly shows us that Jesus’ has his own will that is separate from the Father’s. He is fully human and therefore loves his life and does not want to die. He must surrender to the will of the Father to have the victory. I believe, if we are to give ascent to orthodoxy and accept Jesus as fully human and fully Divine, this must necessarily have been a daily process for him. I see allusions in Scripture and I see an orthodox assertion that together lead me to the conclusion that Jesus had to struggle. He had to choose, against his human will, to submit to the will of the Father.

The Scriptures also tell us that Jesus grew in stature, in wisdom and in favor with God and people. So, that means Jesus learned and matured. It shows us a picture of Jesus as a person in development, in progress. This passage describes his childhood, but I think it’s naive to say that he had fully completed that journey by adulthood. He had to struggle in the desert. He had to face and overcome temptation daily. He had to grieve for John the Baptist and rebuke Peter so that he would not be overcome by temptation. He had to learn and grow and trust that the next idea God was putting in his head was the right one. Jut like we do. If he didn’t have to, he wouldn’t be fully human.

But he showed his Divinity in that he ultimately avoided every pitfall and accomplished what God called him to do. That is why his name is above every other name. Does that give you more of what you’re looking for? Or does it restate what I wrote before? Here’s a list of Scriptures:

Luke 2:52 Jesus grows and learns.

Matthew 4:1-11 Temptation in the desert.

Matthew 16:21-26 Jesus calls Peter a stumbling block and tells Satan to get behind him. In other words, what Peter has said is the kind of thing Satan wants him to believe. They are words that could make Jesus stumble. He then speaks of losing one’s life to find it, something he himself must do. He speaks of his followers denying themselves and taking up their crosses, indicating that to take up his own cross, Jesus too must deny himself. I can’t emphasize enough how important it is to realize that this must necessarily have been an ongoing, human progress. Anything else is a pageant.

Matthew 26:36-46 Gethsemane.

Philippians 2:5-11 Jesus must surrender to have the victory and to be given the name that is above every name.

I hope that helps, Renea. Your thoughts?

- Kevin C. Neece says:

- reneamac says:

November 18, 2011 at 9:57 PM

Yeah, that makes perfect sense! I just didn’t connect the idea of Jesus struggling with his human nature to the phrase “struggled with his dual nature.” That’s a useful way of looking at it I hadn’t really considered. I’m not sure what I thought: that Christ struggled philosophically with his dual nature…? (Which sounds rediculous now that I’m typing it out. ) Now that I realize what you meant, what you meant seems perfectly obvious. Thanks!- Kevin C. Neece says:

November 19, 2011 at 12:33 PM

Oh, good! Sometimes I’m afraid my theology has just become too idiosyncratic or something. It’s nice to make sense!

- Kevin C. Neece says:

- Rebecca Skipper says:

January 9, 2012 at 9:37 PM

i thank everyone for a fascinating discussion. Some of the best examples of human or humanoid struggle occur when Vulcans and Klingons have to survive in the desert. That takes faith and maturity. In some ways, Spock, like Jesus, wasn’t always taken seriously and even mocked when teaching others. Jesus’s death is the obvious example. however, remember how Sarek initially rejected Spock since he was “human?” as seen in “The Final Frontier.”

While i’m a Christian and a Star Trek fan, I feel that StarFleet was in danger of becoming like the Pharacies of Jesus’s day. The fact that the characters had to struggle kept them from becoming too arrogant.

I listened to your wonderful Interview on Matter Stream and understand why Roddenberry rejected some aspects of protestant religion. I believe that the stuggle between good and evil internally and externally is one of the most powerful aspects of Star Trek which should be incorporated into the Humanist philosophy. I do not think humanism and Christianity are at odds. They can complement each other. I think we need to remember that our view of God, technology, and anything we do can be used to glorify God or serve our own ambitions. Remember, Jesus didn’t fit the “mold. Remember how he worked on the Sabbath? I think our own arrogance, the arrogance of Kirk, and the pharacies have some commonalities. they are all so concerned with their “right” way that they will attack anything and anyone,. Look at how Jesus and the Old Testament phrophets were treated. I think diversity and humility are the cure for arrogance. My favorite episodes in Star Trek include Errant of Mercy. The best scenes occur when the characters, in every series, are forced to confront a challenge that tests their avilities and faith. Jesus never shyed away from controversy and faced his death courageously in a way that no one can imagine. If I’ve learned anything from these posts so far it is to Thank God that he reveals His message in the most innovative ways, but some of us are too busy to notice. Thank you for a wonderful post and I look forward to future updates.- Kevin C. Neece says:

January 11, 2012 at 8:08 PM

Thanks for your thoughts, Rebecca. I’m glad you enjoyed the Matter Stream interview! I certainly enjoyed doing it.

I agree with you about the importance of humility. I think Gene Roddenberry would agree as well. He could get a bit proud of himself at times, to be sure. But, one of his favorite phrases was “I don’t know.” I just wish he hadn’t made up his mind about Christianity so strongly and so early.

And you’re right that humanism and Christianity do not have to be at odds! Many humanists are atheists and certainly many (like Roddenberry) reject Christianity, but there is so much value in a humanistic perspective, particularly in reminding us of a view of humanity that contemporary Christianity can lose sight of. We forget, I think, that though the image of God is broken and marred in us, we still bear his image and there is still a human journey before us that is as important as an eternal destination.

I hope you continue to comment and enjoy what we’re doing here. You can sign up for the e-mail newsletter to stay up to date on all things UCP. Thanks for being a part of the conversation!- Rebecca Skipper says:

January 11, 2012 at 8:29 PM

Thank you for commenting on my post. I wish Roddenbury was alive today to read your writings! Perhaps, he’d reconsider his stance on Christianity. One of the strengths, I believe, in any religion, is the ability to reexamine and redefine our worldview based on an evaluation of how much a culture influences religion. I often ask myself if we are conforming Christianity to our worldview or are we trying to live outside this world as Jesus suggests. I think Star Trek was trying to live in a new world and you can’t help but see Christian values portrayed in some aspects of Star Trek particularly the rejection of money for a higher purpose or an emphasis on the rights and dignity of all individuals. Again, thank you for taking the time to comment on my post.

Becky

- Rebecca Skipper says:

- Kevin C. Neece says:

- Thomas Packer says:

July 22, 2012 at 10:48 PM

Interesting discussion. I haven’t watched any Star Trek in years, but for some reason I had the random thought last week that Spock was a Christ figure in Star Trek 2 and 3. Spock’s statement “the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few/one” have stuck with me since the movie came out so many years ago.

Then I thought, surely someone else has seen the parallel. So I googled around a bit and found this page. Kevin has written it very well and added a few points that I had not thought of.

By the way, I agree with Anthony’s statement that Elohim and Yahweh are not exactly synonymous.

Last thought: humanism. It has multiple definitions. In one sense, it is diametrically opposed to Christianity. In another, it is just an orthogonal issue.- Kevin C. Neece says:

July 31, 2012 at 9:08 PM

Thanks for your thoughts, Thomas! I’m glad you had that “random” thought and that your search led you here.

You’re quite right that “humanism” is a somewhat maleable term. And certainly any humanism which ascribes a kind of divinity to humankind (as Roddenberry’s did) does not reflect a Christian worldview. However, I believe that Roddenberry ascribed divinity to humanity because he observed things within our species that reflect our Creator, but had rejected the Hebraic and Christian concept of God. He is surely not alone in this. I also see a humanistic perspective as beneficially informing a Christian worldview because I see our humanity as essential to our faith and our place in God’s world. That’s why I espouse a kind of Christian humanism that recognizes the greatness of humanity, but understands this as a reflection of the greatness of God.

I’m curious as to your thoughts on the names Elohim and Yahweh. They may have slightly different textures of meaning, but they both refer to the same Person. In your view, is one preferable to the other for some reason?

Thanks again for stopping by. There’s more to come. In fact, there are some materials pertaining to Star Trek II, III and IV coming soon that I think you’ll find to be of interest. If you’re not on the mailing list, now’s a good time to sign up. See you around and LLAP!

- Kevin C. Neece says: