For the past couple of years, I've been writing answers on Quora, a website for, well, asking questions. I thought I'd begin sharing my answers here, starting with my latest, to the question, "Was Mr. Rogers a Televangelist to Toddlers?" (Incidentally, the question is in reference to the title of a CNN article by Daniel Burke.)

My Answer From Quora:

I’m rather rankled by Daniel Burke’s use of the term “televangelist” in the CNN piece to which this question refers. It makes for nice alliteration, grabs eyeballs, and alludes to the ministerial nature of Rogers’ work, but it does the latter of these in perhaps too crass a fashion for the subject matter. The term “televangelist” is, of course, fraught with almost nothing but questionable and even criminal figures, from Robert Tilton and Jimmy Swaggert, to Benny Hinn and Joel Osteen. While few televangelists have been convicted of such criminality as Jim Bakker (who, having served his prison time, is back on TV again), most have garnered criticism for lavish lifestyles, unmet promises, false testimonies, hucksterism, and fraud. This is hardly a group to which one could mildly compare Fred Rogers.

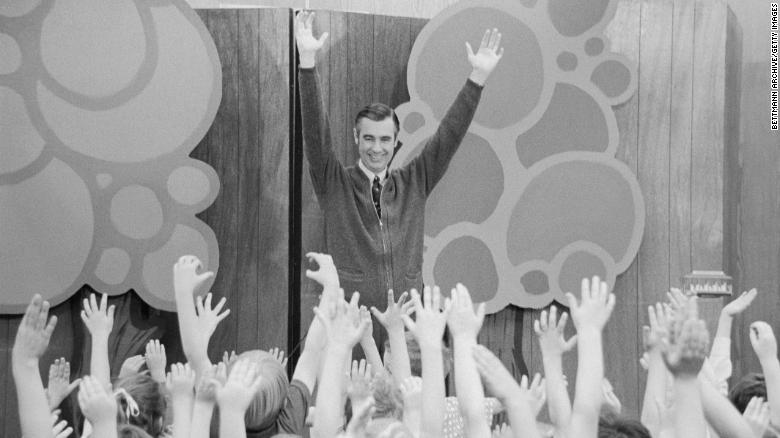

Rogers was, however, perhaps instructive of what the term “televangelist,” despite its somewhat clumsy etymology, should actually mean. Because if “evangelism” is to be understood as sharing God’s good news, Rogers certainly very intentionally engaged in just that. His television program was the ministry to which he was specifically charged when he was ordained by the United Presbyterian Church (UPCUSA) and the sacredness of that duty and calling was never far from—and in fact was constantly present in—Rogers’ mind.

Contrary to what others have noted in their answers, the program was not devoid of mentions of God or of church. They were rare, but they existed. These included, amongst others, a visit to a pretzel factory where it is explained that the shape of the pretzel represents arms folded in prayer and that the three spaces therein represent the three persons of the Trinity,[1] as well as the song, “Creation Duet,” which asserts at length that God is the maker of all things.[2] However, it is true that Rogers had no intention of pushing religion on children, of proselytizing, or of instructing children in religious matters. Still, his moral and spiritual grounding was a Christian one and he drew on many images from that tradition and from the Bible (rainbows, fish, communion, etc.) to share the essential message of Love.

There is a Christian foundation to Rogers’ work that CNN is right to point out. However, I would contend that there is perhaps more that is truly sacred in the Neighborhood program than there is in most of the programs to which the term “televangelism” would be more commonly applied.

On a secondary note, the Neighborhood program’s audience certainly includes toddlers, but it is hardly limited to them. Rogers was always aware that parents were watching too and he intended the program to be viewed and discussed by both children and their parents. While many of the basic ideas in the series are most suited to younger children, there is certainly no ceiling to the age of those who may find solace, wisdom, and hope in the Neighborhood. I, personally, have perhaps gained more from Rogers’ work as an adult than I did as a child—both before and since becoming a parent.

So, in both terms, “Televangelist,” and “Toddlers,” Burke fails to get it quite right here. But the article is good and worth a read, nonetheless.

My Answer From Quora:

I’m rather rankled by Daniel Burke’s use of the term “televangelist” in the CNN piece to which this question refers. It makes for nice alliteration, grabs eyeballs, and alludes to the ministerial nature of Rogers’ work, but it does the latter of these in perhaps too crass a fashion for the subject matter. The term “televangelist” is, of course, fraught with almost nothing but questionable and even criminal figures, from Robert Tilton and Jimmy Swaggert, to Benny Hinn and Joel Osteen. While few televangelists have been convicted of such criminality as Jim Bakker (who, having served his prison time, is back on TV again), most have garnered criticism for lavish lifestyles, unmet promises, false testimonies, hucksterism, and fraud. This is hardly a group to which one could mildly compare Fred Rogers.

Rogers was, however, perhaps instructive of what the term “televangelist,” despite its somewhat clumsy etymology, should actually mean. Because if “evangelism” is to be understood as sharing God’s good news, Rogers certainly very intentionally engaged in just that. His television program was the ministry to which he was specifically charged when he was ordained by the United Presbyterian Church (UPCUSA) and the sacredness of that duty and calling was never far from—and in fact was constantly present in—Rogers’ mind.

Contrary to what others have noted in their answers, the program was not devoid of mentions of God or of church. They were rare, but they existed. These included, amongst others, a visit to a pretzel factory where it is explained that the shape of the pretzel represents arms folded in prayer and that the three spaces therein represent the three persons of the Trinity,[1] as well as the song, “Creation Duet,” which asserts at length that God is the maker of all things.[2] However, it is true that Rogers had no intention of pushing religion on children, of proselytizing, or of instructing children in religious matters. Still, his moral and spiritual grounding was a Christian one and he drew on many images from that tradition and from the Bible (rainbows, fish, communion, etc.) to share the essential message of Love.

There is a Christian foundation to Rogers’ work that CNN is right to point out. However, I would contend that there is perhaps more that is truly sacred in the Neighborhood program than there is in most of the programs to which the term “televangelism” would be more commonly applied.

On a secondary note, the Neighborhood program’s audience certainly includes toddlers, but it is hardly limited to them. Rogers was always aware that parents were watching too and he intended the program to be viewed and discussed by both children and their parents. While many of the basic ideas in the series are most suited to younger children, there is certainly no ceiling to the age of those who may find solace, wisdom, and hope in the Neighborhood. I, personally, have perhaps gained more from Rogers’ work as an adult than I did as a child—both before and since becoming a parent.

So, in both terms, “Televangelist,” and “Toddlers,” Burke fails to get it quite right here. But the article is good and worth a read, nonetheless.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed